Blutner/Philosophy of

Mind/Consciousness

Consciousness

The

greatest gift which humanity has received is free choice. It is true that we

are limited in our use of free choice But the little free choice we have is such

a great gift and is potentially worth so much that for this itself life is

worthwhile living. (Isaac Bashevis Singer 1968)

In many cases we do not do what we will but we will what we do. (Modern

Neuroscience)

1 Libet's 1979 experiments

In the 60s

the brain surgeon Bertram Feinstein allows his friend Benjamin Libet to perform

experiments with uncovered brains. In the breaks during Feinstein’s surgical

work Libet amused the patients by performing simple experiments with electrical

stimulations of certain brain areas, and the patients had to report what they

felt. What is the inner experience of an outer stimulation? In some way, he

began to replicate Wilder Penfield’s investigations about topographic maps

(relating brain and body regions).

However, Libet's main interest was concentrated on the

time characteristics of the relation between external stimulus and

internal experience.

§

His first important finding was that it

needs at least a 500 ms cascade of electrical stimulation to

trigger a conscious experience.

§

In a later experiment Libet and his colleagues

found a very elegant experimental arrangement for investigating the timing of external

stimulus and internal experience:

Libet et al. (1979):

Subjective Referral of the Timing for a Conscious Sensory Experience. Brain

102, 193-224.

The Experiment

More or less simultaneously the experimenter

(1) stimulated a brain region such that the subject felt a tickle in her left

hand.

(2) stimulated the right hand directly.

The subject had to decide where she felt the stimulation first, in the right

hand or in the left hand or at the same time. It was possible for the

experimenter to shift the onsets of the stimulations

Libet’s expectation was that that in each case approximately a half second is

necessary to prompt a conscious experience (since it needs always approximately

a half second before a stimulation can trigger conscious experience). However,

the outcome was completely unexpected:

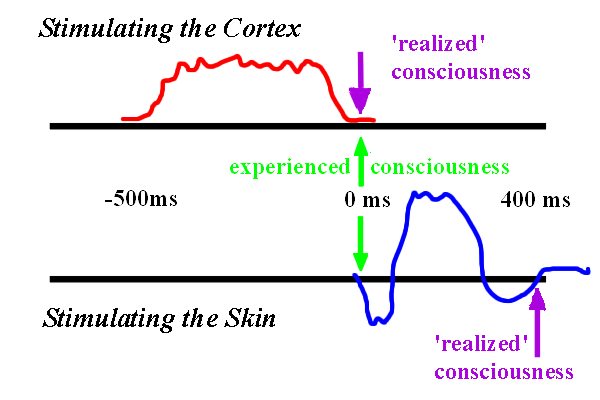

The stimulation of the brain and the stimulation of the skin were experienced

simultaneously if the stimulation of the brain started a half second earlier!

Conclusion

In case of the external stimulation of the skin our

'conscious mind' it subtracts a half second and predates subject's conscious

experience. In this way, we experience the outer world in the correct

way. It takes a while until we experience a event in the outer world.

However, our 'conscious mind' dates it back and we think we experience the

world in the temporally right moment. (The same phenomenon as with the Blind

Spot: Our perceptual system is insufficient. However, we do not become aware

of its errors)

Replication

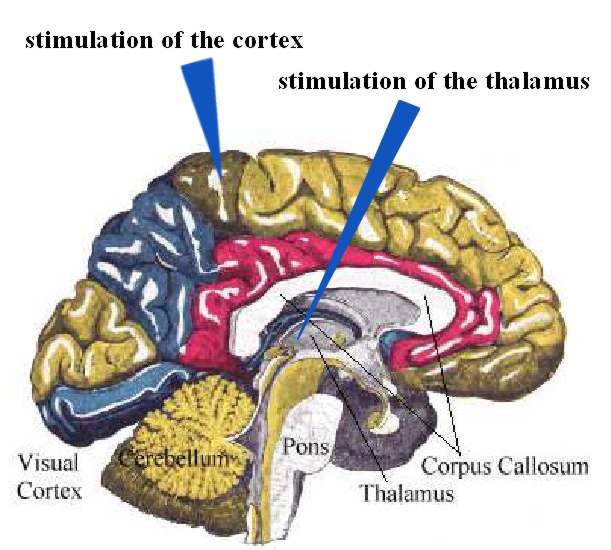

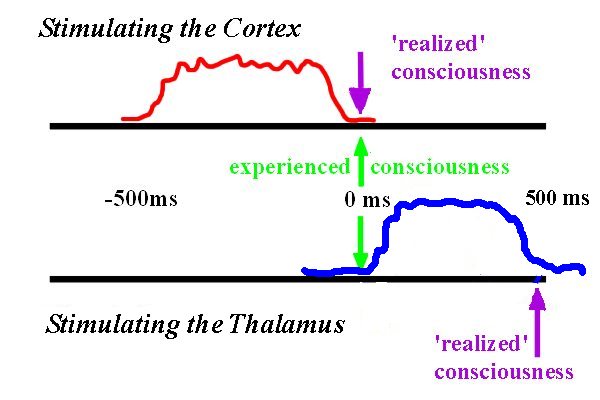

A direct test of this hypothesis is possible if the incommensurability

of the two stimuli (i.e., the direct stimulation of the brain and the

stimulation of the skin) can be overcome. In the critical experiment two

different regions of the brain were stimulated electrically:

(1) a brain region of the cortex such that the subject felt a tickle in her

left hand.

(2) a brain region in the thalamus (phylogenetically old; so-called unspecific

system; this system collects information from the whole body and sends it to

the cortex)

The finding was that in this case very the same pattern is occurring:

2 Is

an experimental approach to the question of free will possible?

The question of free will goes to the root of

our views about human nature and how we relate to the universe and to natural

laws.

§

Are we completely defined by

the deterministic nature of physical laws? Are we essentially sophisticated

automatons only, with our conscious feelings and intentions tacked on as

epiphenomena with no causal power? (cf. Thomas H.Huxley)

§

Or do we have some

independence in making choices and actions, not completely determined by the

known physical laws?

What we need first for approaching the problem in a experimental way is a good operational definition of free will. This approach should be in accord with common views.

That means

§

There should be no external control or cues to

affect the occurrence or emergence of the voluntary act under study; i.e. it

should be endogenous.

§

The subject should feel that he/she wanted to

do it, on her/his own initiative, and feel he could control what is being done,

when to do it or not to do it.

Many actions lack this second attribute. For example, when the primary motor

area of the cerebral cortex is stimulated, muscle contractions can be produced

in certain sites in the body. However, the subject (a neurosurgical patient)

reports that these actions were imposed by the stimulator, i.e. that he did not

will these acts. Clinical disorders with a similar effect are Parkinson and

even obsessive compulsions to act.

Simple examples of 'self

paced' voluntary acts are lifting a finger, closing an eye etc.

How

can we measure the onset of such a voluntary act?

This question is the most important for performing serious experiments.

Obviously, consciousness is private. It is a primary phenomenon. That means

consciousness is only accessible to the subject that has the experience.

(The only criterion for consciousness is consciousness itself). There is

principally no way to reduce it to some measurable activities in he brain. Of

course, there may be a correlation between consciousness and electrical

activity in the brain. However, the primary phenomenon of consciousness is

purely subjective.

Wund's clock

3 Benjamin

Libet on consciousness and free will

Consider the following two description of the same situation, one time as our subjective report, the other time as from the perspective of modern neuroscience.

|

|

A Subjective report |

3.1

The readiness potential

In 1965, Hans

H. Kornhuber and Lüder Deecke investigated the correlation between

arbitrary movements of hand and foot and electrical activities in the brain

(EEG). The general question was this: It is possible to demonstrate by EEG that

a person performs a certain action (for example, she opens or closes her

hand). Kornhuber & Deecke found a rather strange phenomenon:

already 1 second before the hand (or foot) is moved an activity in the EEG

appears. They called it "Bereitschaftspotential" (readiness

potential). Surprising is that the readiness potential starts so early.

Readiness

Potential: Changes of the electrical field of a certain brain region

already 1 second before an action begins.

Benjamin Libet from the Medical centre of the

University of California (San Francisco) was fascinated by this finding and

asked a very important question: If a simple action like moving our hand is prepared

for more than a half second in our brain, at what moment do we consciously

decide to perform this action? Intuitively, we feel it is much less that a half

second. If this is right, and the preparation of an action begins much earlier

as the conscious decision to perform this action, can we have a free will then.

What about the freedom of our will?

3.2

Libet's 1983 experiment

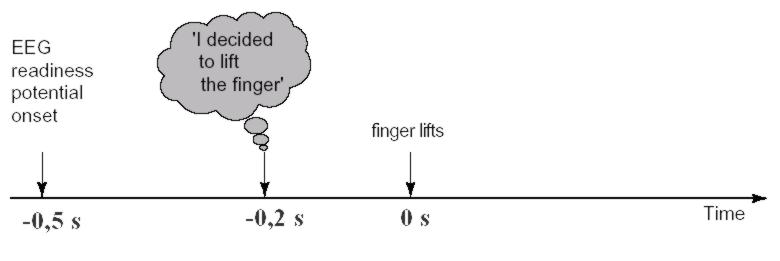

The first experiments to address the timing of decisions directly were conducted by Benjamin Libet and his colleagues.

Libet et al. (1983): Time of conscious intention to act in relation

to onset of cerebral activity (readiness potential): the unconscious initiation

of a freely voluntary act. Brain 106, 623–642.

Their experiments asked questions about

when people believed they made a decision versus when the brain began to make

the decision. In one form of their experiment, they measured EEG activity while

subjects voluntarily chose to lift a finger. During the task, subjects watched

a rapidly moving clock hand and made a mental note of when they decided to lift

their finger.

This yielded three types of data:

(1)

when the subject lifted her finger [electromyogram of the muscles]

(2) when she believed she decided to lift her finger [Wund's clock]

(3) what her brain activity was during this time. [EEG]

The EEG results demonstrated that the cortex became active with a ‘readiness

potential’ 350 ms before the reported awareness of a ‘wish to move’. These

experiments suggested that our subjective awareness of decisions occurs

measurably later than the actual events of deciding

Conclusion

Our brain

initiates a 'voluntionary act' unconsciously. Not a conscious decision

but unconscious processes are at the beginning. This conclusions directly

contradicts our (conscious) common sense: Consciousness is unfaithful. It

swindles people. Furthermore, from the voluntionary act to the action (lifting

a finger) it takes about 200 ms (myogram of the muscles). Is this enough time

for a conscious stop of the action?

3.3

Libet's conclusions concerning free will

§

Actually, only 100 ms is

available in which the conscious function might affect the final outcome of the

volitional process (the primary motor cortex needs some time to the spinal

motor nerve cells).

§

Libet argues that this is

enough time for stopping or voting the final progress of the volitional

process. "Conscious-will could thus affect the outcome of the volitional

process even though the latter was initiated by unconscious cerebral

processes."

§

Indirect evidence of a veto

possibility: Subjects in Libet's experiment reported that a conscious wish

appeared but that they suppressed or vetoed that. Libet could show that in such

cases a large readiness potential proceeded the veto, signifying that the

subject was indeed preparing the act, even thought the action was aborted by

the subject.

§

Does the conscious veto have

a preceding unconscious origin? In this case we cannot consider the veto

as action of free will. Libet proposes, instead, that the conscious veto

may not require preceding unconscious processes. The conscious veto is a control

function different from a conscious wish to act. At the moment there is no

experimental evidence against this possibility.

§

Psychological implication:

Consciousness is not a high level authority that gives orders to subordinated

instances. Instead, its main role is a selective one: make a decision

between the bulk of possibilities that are proposed by unconscious

processes.

§

Ethical implication: The role

of conscious free will is not to initiate a voluntary act, but rather to

control whether the act takes place. "This kind of role for free

will is actually in accord with religious and ethical strictures. These

commonly advocate that you 'control yourself'. Most of the Ten Commandments are

'do not' orders"

4

Causality and the perception of time

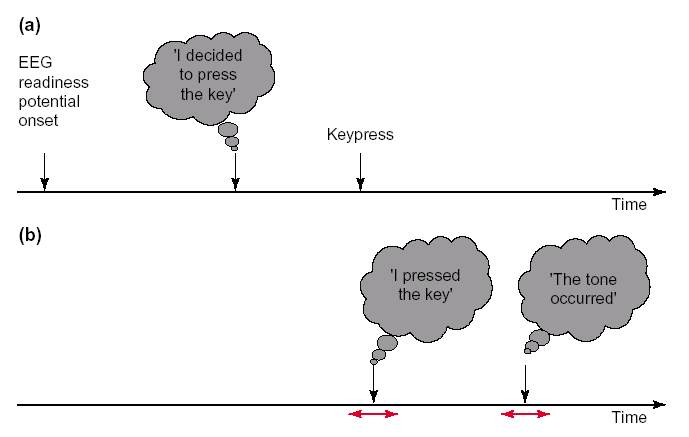

Libet investigated the relation between the

felt time of conscious actions/events and the time course of brain activity

(a). Another important question concerns the perception of events in time

dependent on the real time course, for example the timing judgment of

pressing a key and the (delayed) occurrence of a tone (b).

An especially interesting question concerns the interaction of time and

causality. What is the relation between time and causality? Does our perception

of when an event occurs depend on whether we caused it? A recent study by

Haggard, Clark and Kalogeras (2002) suggests that when we perceive our actions

to cause an event, it seems to occur earlier than if we did not cause it

(cf. David M. Eagleman and Alex O. Holcombe, in the reader)

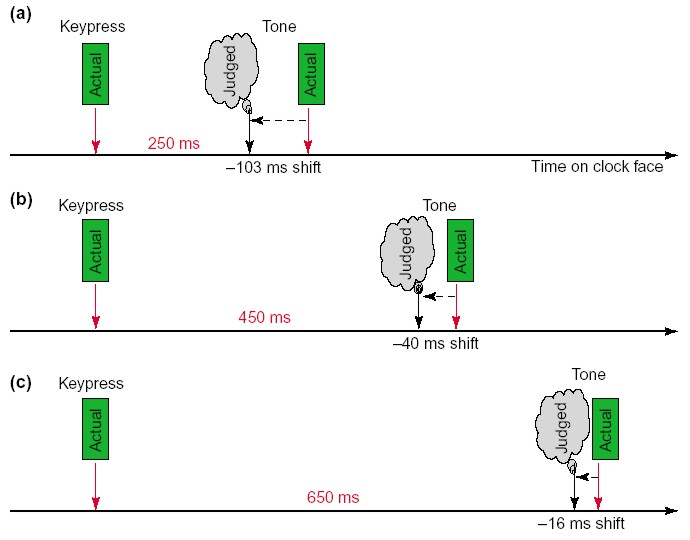

In one condition, subjects judged the timing of an auditory tone by reporting

the corresponding position of a rapidly moving clock hand. In the second,

crucial condition, subjects pressed a key that caused a tone to follow 250 ms

later. Again, subjects judged the time of the tone. Comparing the data across

conditions, the perceived times of the tone when keypress and ton were causally

linked were compared with the conditions in which the ton occurred by itself.

Remarkably, when the tone was causally linked to the subjects’ keypress,

subjects judged the tone to occur 46 ms earlier than if these events had

occurred alone.

In a second experiment with different subjects, the delay between the keypress

and subsequent tone was varied (to be 250, 450, or 650 ms), and subjects judged

the time of the tone. Haggard et al. found that the further apart the keypress

and tone, the more the temporal ‘attraction’ of the tone to the keypress was

diminished (see Figure).

Conclusion

Tones perceived to be a consequence of one’s actions seem to occur earlier in

time than solitary tones. More generally, when we perceive our actions to cause

an event, it seems to occur earlier than if we did not cause it.

Eagleman & Holcombe's explanation

The philosopher David Hume pointed out that events that are close together in

space and time are more likely than spatio-temporally distant events to be

perceived as causally related. With certain assumptions about the prior

probabilities, it follows from Bayes’ equation that events known

to be causally related are more likely to be close in time and space than

unrelated events.

P(Cause (e1, e2) | CloseTime(e1, e2)) >

P(Cause (e1, e2) | DistantTime(e1, e2))

==> (with certain assumptions about the prior probabilities)

P(CloseTime(e1, e2) | Cause (e1, e2)) >

P(DistantTime(e1, e2) | Cause (e1, e2))